|

Parkinson's

Disease is due to the insufficient formation and action of dopamine. Human

beings have always had the potential for insufficient dopamine. So

although Parkinson's Disease has increased in its prevalence over time, it

must have existed to some extent for as long as human beings. There are

references to Parkinson's Disease symptoms throughout history.

Ancient HISTORY

An ancient

civilisation in India practiced their medical doctrine called Ayurveda.

Ayurveda is claimed to be a divine revelation of the ancient Indian

creator God Lord Brahma.

It describes

the symptoms of Parkinson's Disease, which they called Kampavata as far back as

5000 B.C.. To treat Kampavata, they used a tropical legume called Mucuna Pruriens,

which is a natural source of

therapeutic quantities of L-dopa. Mucuna pruriens is the oldest known

method of treating Parkinson's Disease, and is still being

used today. An ancient

civilisation in India practiced their medical doctrine called Ayurveda.

Ayurveda is claimed to be a divine revelation of the ancient Indian

creator God Lord Brahma.

It describes

the symptoms of Parkinson's Disease, which they called Kampavata as far back as

5000 B.C.. To treat Kampavata, they used a tropical legume called Mucuna Pruriens,

which is a natural source of

therapeutic quantities of L-dopa. Mucuna pruriens is the oldest known

method of treating Parkinson's Disease, and is still being

used today.

The Huang di nei

jing su wen (often known as the Su wen), is the oldest existing Chinese

medical text. It was written in around 500 B.C..

It is composed of two texts

each of eighty one chapters or treatises in a question and answer format

between the mythical Huang di (Yellow

Emperor) and his ministers.

The first text, the Suwen, also

known as Plain Questions, covers the theoretical foundation of

Chinese Medicine, diagnosis methods and

treatment methods.

It also describes the symptoms of Parkinson�s Disease. The Huang di nei

jing su wen (often known as the Su wen), is the oldest existing Chinese

medical text. It was written in around 500 B.C..

It is composed of two texts

each of eighty one chapters or treatises in a question and answer format

between the mythical Huang di (Yellow

Emperor) and his ministers.

The first text, the Suwen, also

known as Plain Questions, covers the theoretical foundation of

Chinese Medicine, diagnosis methods and

treatment methods.

It also describes the symptoms of Parkinson�s Disease.

It

is claimed that there are references to the symptoms of Parkinson�s

Disease in both the old and new testaments of the Bible. Often cited as

possible references to Parkinsonism is the following depiction of old age

in the Old Testament : "When the guardians of the house tremble, and the

strong men are bent" (Ecclesiastes 12 : 3), and the following description

in the New Testament "There was a woman who for eighteen years had been

crippled by a spirit.....bent and completely incapable of standing erect"

(Luke 13:11). It

is claimed that there are references to the symptoms of Parkinson�s

Disease in both the old and new testaments of the Bible. Often cited as

possible references to Parkinsonism is the following depiction of old age

in the Old Testament : "When the guardians of the house tremble, and the

strong men are bent" (Ecclesiastes 12 : 3), and the following description

in the New Testament "There was a woman who for eighteen years had been

crippled by a spirit.....bent and completely incapable of standing erect"

(Luke 13:11).

ANCIENT GREEKS

In

the Illiad, which, along with the Odyssey are claimed to have been written

by the ancient Greek author Homer in the eighth century B.C., the septuagenarian King Nestor

describes symptoms that appear to be those of Parkinson's Disease. King

Nestor

remarks that, despite the fact he still partakes of the armed struggle, he

can no longer compete in athletic contests. He wrote that : my limbs are no longer

steady, my friend, nor my feet, neither do my arms, as they once did,

swing light from my shoulders. In

the Illiad, which, along with the Odyssey are claimed to have been written

by the ancient Greek author Homer in the eighth century B.C., the septuagenarian King Nestor

describes symptoms that appear to be those of Parkinson's Disease. King

Nestor

remarks that, despite the fact he still partakes of the armed struggle, he

can no longer compete in athletic contests. He wrote that : my limbs are no longer

steady, my friend, nor my feet, neither do my arms, as they once did,

swing light from my shoulders.

Erasistratus

of Ceos (310BC- 250BC) was a Greek anatomist and royal physician under

Seleucus I Nicator of Syria. Along with fellow Greek Philosopher

Herophilus, he founded a school of

anatomy in

Alexandria. Caelius Aurelianus wrote that Erasistratus of Ceos appeared to be describing the freezing that occurs in

Parkinson's Disease when he termed paradoxos a type of paralysis in which

a person walking along must suddenly stop and cannot go on, but after a

while can walk again. Erasistratus

of Ceos (310BC- 250BC) was a Greek anatomist and royal physician under

Seleucus I Nicator of Syria. Along with fellow Greek Philosopher

Herophilus, he founded a school of

anatomy in

Alexandria. Caelius Aurelianus wrote that Erasistratus of Ceos appeared to be describing the freezing that occurs in

Parkinson's Disease when he termed paradoxos a type of paralysis in which

a person walking along must suddenly stop and cannot go on, but after a

while can walk again.

ANCIENT ROME

Aulus

Cornelius Celsus (c25BC-c50AD), although apparently not a physician

himself, compiled an encyclopedia entitled De artibus (25AD-35AD) that

included De medicina octo libri (The Eight Books of Medicine).

He advised

against administering those who suffered tremor of the sinews with emetics

or drugs that promoted urination, and also against baths and dry sweating.

Fine

tremor was distinguished from a coarser shaking, which was independent of

voluntary motion. So it resembled resting tremor. It could be alleviated

by the application of heat and by bloodletting. Aulus

Cornelius Celsus (c25BC-c50AD), although apparently not a physician

himself, compiled an encyclopedia entitled De artibus (25AD-35AD) that

included De medicina octo libri (The Eight Books of Medicine).

He advised

against administering those who suffered tremor of the sinews with emetics

or drugs that promoted urination, and also against baths and dry sweating.

Fine

tremor was distinguished from a coarser shaking, which was independent of

voluntary motion. So it resembled resting tremor. It could be alleviated

by the application of heat and by bloodletting.

Pedanius

Dioscorides (c40-c90)

was an ancient

Greek

physician,

pharmacologist and

botanist from Anazarbus,

Cilicia,

Asia Minor, who practised in

ancient Rome during the time of

Nero. Dioscorides is famous for writing

De

Materia Medica, which is a precursor to

all modern

pharmacopeias, and is one of the most

influential herbal books in history. Dioskorides wrote that beaver

testes, prepared with vinegar and roses was helpful not only for the "lethargicall"

but was also good for tremblings and convulsions, and for all diseases of

the Nerves, being either drank or anointed on, and that it had a warming

faculty. Pedanius

Dioscorides (c40-c90)

was an ancient

Greek

physician,

pharmacologist and

botanist from Anazarbus,

Cilicia,

Asia Minor, who practised in

ancient Rome during the time of

Nero. Dioscorides is famous for writing

De

Materia Medica, which is a precursor to

all modern

pharmacopeias, and is one of the most

influential herbal books in history. Dioskorides wrote that beaver

testes, prepared with vinegar and roses was helpful not only for the "lethargicall"

but was also good for tremblings and convulsions, and for all diseases of

the Nerves, being either drank or anointed on, and that it had a warming

faculty.

Symptoms of Parkinson�s Disease were described by the ancient Greek

physician Galen (129-200) who worked in ancient Rome. He wrote of tremors

of the hand at rest.

He wrote extensively on disorders of

motor function, including

the book On tremor, palpitation, convulsion and

shivering. He distinguished between forms of shaking of the limb on the

basis of origin and appearance. The aged, he noted, exhibited tremor

because of a decline in their power to control motion of

their limbs. The key to overcoming tremor was to abolish the proximal

cause, but for the aged, this was impractical. Symptoms of Parkinson�s Disease were described by the ancient Greek

physician Galen (129-200) who worked in ancient Rome. He wrote of tremors

of the hand at rest.

He wrote extensively on disorders of

motor function, including

the book On tremor, palpitation, convulsion and

shivering. He distinguished between forms of shaking of the limb on the

basis of origin and appearance. The aged, he noted, exhibited tremor

because of a decline in their power to control motion of

their limbs. The key to overcoming tremor was to abolish the proximal

cause, but for the aged, this was impractical.

MEDIEVAL

HISTORY

Paul

of Aigina (c625-c690) the

Byzantine Greek

physician, wrote the

medical encyclopedia "Medical

Compendium in Seven Books". For many years in the

Byzantine Empire, this work contained the

sum of all

Western medical knowledge and was

unrivaled in its accuracy and completeness. Paul of Aegina noted in his

work On trembling that tremor was characteristic of alcoholism and what

Mettler interpreted as "senile paralysis agitans". Paul

of Aigina (c625-c690) the

Byzantine Greek

physician, wrote the

medical encyclopedia "Medical

Compendium in Seven Books". For many years in the

Byzantine Empire, this work contained the

sum of all

Western medical knowledge and was

unrivaled in its accuracy and completeness. Paul of Aegina noted in his

work On trembling that tremor was characteristic of alcoholism and what

Mettler interpreted as "senile paralysis agitans".

An

ancient Syrian medical text listed for nervous

diseases a complex unguent for "pains in the excretory organs and in the

joints, and in cases of gout and palsy, and for those who have the

tremors, and for all the pains which take place in the nerves". It

consists of thirty-five components, including frankincense, rosemary,

several types of cypress, cardamom, peppercorns, myrrh, mandragora and

frogs. It was to rubbed on the paralysed or rigid limb. An

ancient Syrian medical text listed for nervous

diseases a complex unguent for "pains in the excretory organs and in the

joints, and in cases of gout and palsy, and for those who have the

tremors, and for all the pains which take place in the nerves". It

consists of thirty-five components, including frankincense, rosemary,

several types of cypress, cardamom, peppercorns, myrrh, mandragora and

frogs. It was to rubbed on the paralysed or rigid limb.

Ibn Sina

(c980-1037), the Persian polymath and foremost physician of his time

discussed the various forms of motor unrest

in his chapter on nervous disorders in the "Canon of Medicine". The

description of tremor is not unexpectedly similar to that of Galen, as it

was based on previous works including that of Galen. A range of measures

are proposed according to the cause of the disorder. Bathing in sea-water

or mineral baths (nitrate, arsenic, asphalt, sulphur) was recommended,

as was the ever popular evacuation; composite preparations including made

from the excretion of the anal gland of the beaver mixed with honey and cold oil, to which pills formed

from rue (Ruta graveolens) and scolopendrium (Scolopendrium vulgare;

hart's tongue). Ibn Sina

(c980-1037), the Persian polymath and foremost physician of his time

discussed the various forms of motor unrest

in his chapter on nervous disorders in the "Canon of Medicine". The

description of tremor is not unexpectedly similar to that of Galen, as it

was based on previous works including that of Galen. A range of measures

are proposed according to the cause of the disorder. Bathing in sea-water

or mineral baths (nitrate, arsenic, asphalt, sulphur) was recommended,

as was the ever popular evacuation; composite preparations including made

from the excretion of the anal gland of the beaver mixed with honey and cold oil, to which pills formed

from rue (Ruta graveolens) and scolopendrium (Scolopendrium vulgare;

hart's tongue).

SIXTEENTH CENTURY

|

The

Italian artist, engineer and scientist Leonardo da Vinci (1452-1519) also

studied anatomy, physiology and medicine. Leonardo da Vinci kept secret notebooks

in which he wrote and sketched his ideas and observations. He saw people

whose symptoms coincided with the tremors seen in Parkinson's Disease.

Leonardo wrote in his notebooks that "you will see.....those who.....move

their trembling parts, such as their heads or hands without permission of

the soul; (the) soul with all its forces cannot prevent these parts from

trembling." |

| |

|

|

There are examples of references to the symptoms of Parkinson's

Disease in the plays of the English playwright William Shakespeare

(1564-1616). There is a reference to shaking palsy in the second

part of his historical play Henry VI, during an exchange between

Dick and Say. Say explains to Dick that it is shaking palsy rather

than fear that was causing his shaking. Dick asks Say : "Why dost

thou quiver, man ?" Say responds : "The palsy, and not fear,

provokes me." Shaking palsy was the old name for Parkinson's

Disease symptoms.

|

| |

|

|

John Gerard (1545-1611/12)

was an

English

botanist famous for his

herbal garden. He studied medicine and

travelled widely as a ship's

surgeon. In

1597, he published a list of plants

cultivated in his

garden at

Holborn. It was basically a translation

of a 1583 Latin herbal illustrated. he writes of Sage

that it "strengthneth the sinewes, restoreth health to those that have the

palsie upon a moist cause, takes away shaking or trembling of the

members". He also mentioned cabbage, pellitory and mugwort for treating

trembling of the sinews. |

SEVENTEENTH CENTURY

|

Nicholas

Culpeper (1616-1654) was an English botanist, herbalist, physician and

astrologer. In his book

Complete Herbal he suggests sage

for "sinews, troubled with palsy and cramp". Amongst other

plant remedies Culpepper suggested for palsy and trembling were

bilberries, briony (called "English mandrake"), and mistletoe. In his

Pharmacopoeia Londinensis, a variety

of substances were claimed to be useful in the

treatment of "palsies", the "dead

palsy", and "tremblings". These included "oil of winged ants" and

preparations including earthworms. |

| |

|

|

The

writer and antiquary, John Aubrey (1626-1697) wrote a biography of the

philosopher Thomas

Hobbes (1588-1679) titled "Life of Mr Thomas Hobbes of Malmesbury".

In it, he used the

term "Shaking

Palsey" in his description of the progressive disability that had afflicted Thomas Hobbes.

John Aubrey wrote

of Thomas Hobbes that he "had the shaking Palsey in his hands.....and has grown upon him in degrees", and that

".....Mr Hobbs wase for severall yeares before he died so Paralyticall

that he wase scarce able to write his name". |

| |

|

|

The

Hungarian doctor Ferenc P�pai P�riz (1649-1716) described in 1690 in his medical text Pax Corporis all four cardinal signs

of Parkinson's Disease :

tremor, bradykinesia, rigor and postural instability. This was the first

time that all the main symptoms of Parkinson's Disease have been formally

described. The book was only published in Hungarian, which has resulted in his description of

Parkinson's Disease being ignored in the medical literature in favour of

later descriptions of Parkinson's Disease wrongly being claimed to be the

first.

|

EIGHTEENTH CENTURY

|

George Cheyne

(1671-1743) was a Scottish physician, psychologist, philosopher and

mathematician. It is possible to interpret

a disorder described in chapter XII of his The English Malady (1734) as

parkinsonian. The subject of his discussion is the vaguely defined

"Palsy", or "Paralytick Symptoms". "Palsy" was then defined as "a disease

wherein the body, or some of its members lose their motion, and sometimes

their sensation of feeling. The disease is never acute, often tedious, and

in old people, almost incurable. |

| |

|

|

Francois Boissier

de Sauvages de la Croix (1706-1767) provided one of the clearest

descriptions of a parkinsonism-like condition in 1763. He spoke of a

condition that he named "sclerotyrbe festinans" in which decreased

muscular flexibility led to difficulties in the initiation of walking.

Both of the cases he observed were in elderly people. His observations,

along with those of Jerome David Gaubius

(1705-1780) and Franciscus de la Bo� (1614-1672)

were subsequently cited by James Parkinson. |

| |

|

|

John

Hunter (1728-1793) was a distinguished Scottish surgeon. In his Croonian

lecture in 1776, John Hunter gave a description of Lord L. that was

similar to paralysis agitans. He wrote that "Lord L's hands are almost

perpetually in motion, and he never feels the sensation in them of being

tired. When he is asleep his hands, &c., are perfectly at rest; but when

he wakes in a little time they begin to move". It has been suggested that

James Parkinson may have attended this lecture. |

james parkinson

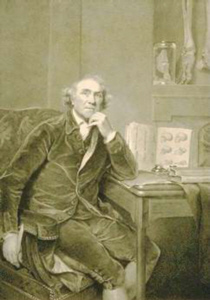

Parkinson's

disease was first formally described in modern times in

"An Essay on the

Shaking Palsy," published

in 1817 by a London physician named

James Parkinson (1755-1824). James Parkinson

described the medical

history of six

individuals in London who had symptoms of the disease that eventually bore his name.

Unusually for such a description, he did not actually examine all these patients

himself but observed them on daily walks.

The purpose of his essay was to

document the symptoms of the medical disorder, which he described as

"Involuntary tremulous motion, with lessened muscular power, in parts not in

action and even when supported; with a propensity to bend the trunk

forwards, and to pass from a walking to a running pace : the senses and

intellect being uninjured." Parkinson's

disease was first formally described in modern times in

"An Essay on the

Shaking Palsy," published

in 1817 by a London physician named

James Parkinson (1755-1824). James Parkinson

described the medical

history of six

individuals in London who had symptoms of the disease that eventually bore his name.

Unusually for such a description, he did not actually examine all these patients

himself but observed them on daily walks.

The purpose of his essay was to

document the symptoms of the medical disorder, which he described as

"Involuntary tremulous motion, with lessened muscular power, in parts not in

action and even when supported; with a propensity to bend the trunk

forwards, and to pass from a walking to a running pace : the senses and

intellect being uninjured."

THE FIRST CLAIMED CURE

English physician John

Elliotson (1791-1868) published pamphlets concerning the disorder from

1827 to 1831 in the Lancet, which largely consisted of case reports. Amongst his

preferred methods of treatment were bleeding, induction and maintenance of

pus building, cauterization, purging, low diet and mercurialization,

silver nitrate, arsenic, zinc sulphate, copper compounds, and the

administration of iron as a tonic with some porter, which is a kind of

dark beer. Elliotson made the first known claimed cure. He suggested that many young patients could be

cured using the carbonate of iron. On another

occasion, he reported that the �disease instantly and permanently gave

way� when he treated with iron a patient who had proved resistant to all

other forms of therapy. This was well over a century before iron was found

to be essential for the formation of L-dopa. English physician John

Elliotson (1791-1868) published pamphlets concerning the disorder from

1827 to 1831 in the Lancet, which largely consisted of case reports. Amongst his

preferred methods of treatment were bleeding, induction and maintenance of

pus building, cauterization, purging, low diet and mercurialization,

silver nitrate, arsenic, zinc sulphate, copper compounds, and the

administration of iron as a tonic with some porter, which is a kind of

dark beer. Elliotson made the first known claimed cure. He suggested that many young patients could be

cured using the carbonate of iron. On another

occasion, he reported that the �disease instantly and permanently gave

way� when he treated with iron a patient who had proved resistant to all

other forms of therapy. This was well over a century before iron was found

to be essential for the formation of L-dopa.

The first named patient

Wilhelm von Humboldt (1767-1835), a

philosopher and diplomat, described in his letters from 1828 until his

death in 1835, his own medical history,

which gave a more complete description of the symptoms of Parkinson's Disease than had James Parkinson. They included resting tremor

and especially problems in writing, called by him "a special clumsiness"

that he attributed to a disturbance in executing rapid complex movements.

In addition to lucidly describing akinesia, he was also the first to

describe micrographia. He furthermore noticed his typical parkinsonian

posture. There were incidental references in the following decades to what

may (or may not) have been some of the symptoms of Parkinson�s Disease by

Toulmouche (1833), Hall (1836, 1841), Elliotson (1839), Romberg (1846). However, the syndrome remained hardly known. Wilhelm von Humboldt (1767-1835), a

philosopher and diplomat, described in his letters from 1828 until his

death in 1835, his own medical history,

which gave a more complete description of the symptoms of Parkinson's Disease than had James Parkinson. They included resting tremor

and especially problems in writing, called by him "a special clumsiness"

that he attributed to a disturbance in executing rapid complex movements.

In addition to lucidly describing akinesia, he was also the first to

describe micrographia. He furthermore noticed his typical parkinsonian

posture. There were incidental references in the following decades to what

may (or may not) have been some of the symptoms of Parkinson�s Disease by

Toulmouche (1833), Hall (1836, 1841), Elliotson (1839), Romberg (1846). However, the syndrome remained hardly known.

The naming of Parkinson's Disease

It was not until 1861 and 1862 that

Jean-Martin Charcot (1825-1893) with Alfred Vulpian (1826-1887) added

more symptoms to James Parkinson's clinical description, and

then subsequently confirmed James Parkinson's place in medical history by

attaching the name Parkinson's Disease to the syndrome.

Charcot added to the list of symptoms the mask face, various forms of

contractions of hands and feet, akathesia as well as rigidity. It was only after Charcot gave a clinical lesson

in 1868 that the difference became clear (Charcot, 1868). In 1867 Charcot

introduced a treatment with the alkaloid drug hyoscine (or scopolamine)

derived from the Datura plant, which was used until the advent of L-Dopa a century later. In 1876 Charcot described a patient suffering from

Parkinson's disease in the absence of tremor, while rigidity was present. In

this case there was no paralysis, so Charcot rejected the term paralysis

agitans. Instead he suggested that the disease be referred to in future as

Parkinson's disease. Charcot added to the list of symptoms the mask face, various forms of

contractions of hands and feet, akathesia as well as rigidity. It was only after Charcot gave a clinical lesson

in 1868 that the difference became clear (Charcot, 1868). In 1867 Charcot

introduced a treatment with the alkaloid drug hyoscine (or scopolamine)

derived from the Datura plant, which was used until the advent of L-Dopa a century later. In 1876 Charcot described a patient suffering from

Parkinson's disease in the absence of tremor, while rigidity was present. In

this case there was no paralysis, so Charcot rejected the term paralysis

agitans. Instead he suggested that the disease be referred to in future as

Parkinson's disease.

THE FIRST KNOWN

DEPICTIONS OF PARKINSON'S DISEASE

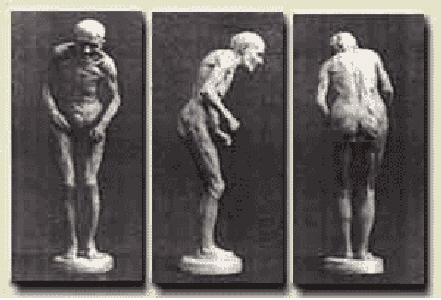

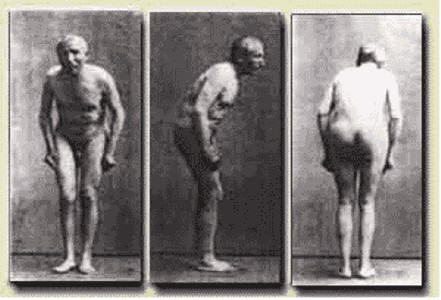

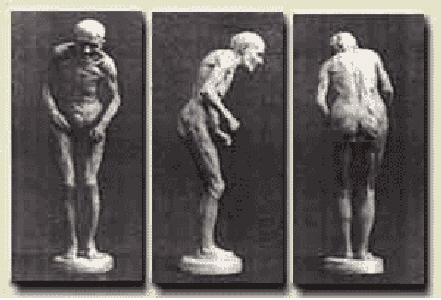

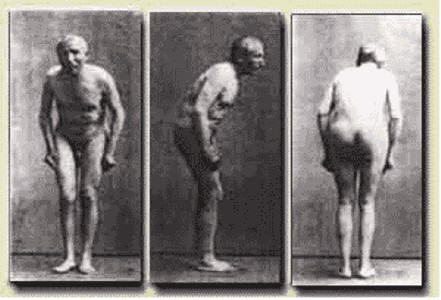

Paul Marie Louis

Pierre Richer (1849-1933) was a French anatomist, physiologist, sculptor and

anatomical artist. Paul Richer was an assistant to Jean-Martin Charcot at

the Salp�tri�re. In 1880, Jean-Marie Charcot completed a full clinical

description of Parkinson's Disease. The symptoms were depicted by Paul

Richer in drawings and a statuette of people with Parkinson's Disease.

Along with a photograph, these

are the first known depictions of Parkinson's Disease.

THE USE OF

ELECTROTHERAPY

In 1868

French doctor Guillame Benjamin-Amand Duchenne

(1806-1875),

had reported a case in which he had cured paralysis agitans by application

of galvanism.

Duchenne had

popularized the

use of electrical means with his 1855 publication "On localized

electrification, and on its application to pathology

and

therapy".

Irish physician

U.S.L.Butler also claimed in 1869 that it cured a patient of paralysis

agitans.

Hughlings Jackson, and William Gowers in

1893, who also tried it in paralysis agitans, were unstinting in their

deprecation of the practice as "useless".

Despite this, electrical stimulation

in Parkinson�s disease continued to be used for decades more. In the 1924

edition of his handbook on electrotherapy, Toby Cohn commented that

"remarkable results could not be expected", and that what benefits he had

seen were largely psychological. In his 1941 review of the "modern treatment

of parkinsonism", Critchley specifically warned against electricity and

other spurious claims of curing the disease. Irish physician

U.S.L.Butler also claimed in 1869 that it cured a patient of paralysis

agitans.

Hughlings Jackson, and William Gowers in

1893, who also tried it in paralysis agitans, were unstinting in their

deprecation of the practice as "useless".

Despite this, electrical stimulation

in Parkinson�s disease continued to be used for decades more. In the 1924

edition of his handbook on electrotherapy, Toby Cohn commented that

"remarkable results could not be expected", and that what benefits he had

seen were largely psychological. In his 1941 review of the "modern treatment

of parkinsonism", Critchley specifically warned against electricity and

other spurious claims of curing the disease.

Expanding the known symptoms

After Charcot

initiated the research of incomplete forms of Parkinson's disease, rigidity

as a symptom grew in importance. In 1892 B�chet

made the remark that all symptoms of Parkinson's disease were secondary

to rigidity,

tremor being an

exception.

Although Charcot and Parkinson pointed out that

patients are moving slowly and with difficulty, they did not see this as a

symptom in its own right. The slowness of movement was firstly taken into

account by Claveleira and it became a new element of the definition. Jaccoud referred to this symptom in 1873 as akinesia.

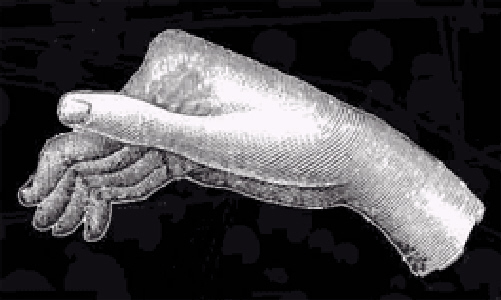

In 1886, the neurologist and artist, Sir William Richard Gowers, drew an

illustration in 1886 as part of his documentation of Parkinson's Disease.

Cruchet introduced the word bradykinesia and emphasized that this symptom

should be mentioned in any definition of Parkinson's

disease.

Jules

Froment, a French neurologist, contributed to the study of

parkinsonian rigidity during the 1920s. Although Charcot and Parkinson pointed out that

patients are moving slowly and with difficulty, they did not see this as a

symptom in its own right. The slowness of movement was firstly taken into

account by Claveleira and it became a new element of the definition. Jaccoud referred to this symptom in 1873 as akinesia.

In 1886, the neurologist and artist, Sir William Richard Gowers, drew an

illustration in 1886 as part of his documentation of Parkinson's Disease.

Cruchet introduced the word bradykinesia and emphasized that this symptom

should be mentioned in any definition of Parkinson's

disease.

Jules

Froment, a French neurologist, contributed to the study of

parkinsonian rigidity during the 1920s.

ENCEPHALITIS

LETHARGICA

In 1915,

epidemics of Encephalitis Lethargica broke out around the world. It was

first described in 1917 by the Austrian neurologist Constantin von Economo.

It started off as an influenza like fever, and then developed in to

symptoms such as headache, depression, delirium, confusion, motor

disturbances, psychosis and stupor.

Its

symptoms were thought to encompass

almost anything imaginable. Encephalitis Lethargica could cause death in a

short period, or a type of sleep that might last days, weeks or months,

but could also cause insomnia. Many of those that survived developed Postencephalitic Parkinsonism. Encephalitis Lethargica consequently led to

a huge increase in the number of people with Parkinsonism. In the 1920's,

the majority of Parkinsonian patients had Postencephalitic Parkinsonism. Its

symptoms were thought to encompass

almost anything imaginable. Encephalitis Lethargica could cause death in a

short period, or a type of sleep that might last days, weeks or months,

but could also cause insomnia. Many of those that survived developed Postencephalitic Parkinsonism. Encephalitis Lethargica consequently led to

a huge increase in the number of people with Parkinsonism. In the 1920's,

the majority of Parkinsonian patients had Postencephalitic Parkinsonism.

THE USE OF

ALKALOIDS

The first

widespread use of the alkaloid atropine was in the 1920's. High dose

atropine therapy dominated in the first half of the 1930's, achieving

significant results, but it was accompanied by serious side effects. In

1926, the Bulgarian Ivan Raeff introduced in to the treatment of post

encephalitic Parkinsonism what was later called the "Bulgarian treatment",

which was white wine extract of the belladonna root. It was the belladonna

root that was the effective part. The alkaloid content of the extract

included varying amounts of hyoscyamine, atropine and, in lesser

quantities, scopolamine and belladonnine. By the beginning of the 1940's

most patients were being treated using belladonna alkaloids.

THE USE OF

NEUROSURGERY

The first

specific attempt to treat Parkinsonism surgically was reported by Leriche

in 1912, via section of the posterior roots. The method relieved tremor or

rigidity. Improvements in tremor were subsequently

achieved by cortectomy, but often at the price of other functional losses.

Cordotomy was directed against unilateral tremor and rigidity, and

associated with fewer side effects. Meyers reported in 1951 that

sectioning of pallidofugal fibres achieved the best results for relieving

tremor and rigidity, but most surgeons chose to undertake a more direct

attack on the pallidum, with equal success and a lower fatality rate. The thalamus gradually

became the preferred target, as the impact on tremor was greater and the

operation was safer. After a sharp decline in stereotactic surgery,

thalamotomy was revived in the 1970's for tremor that was not

helped by L-dopa.

NEW SYNTHETIC

DRUGS

During the

1950's, synthetic drugs became the main methods of treating Parkinson's

Disease. Due to their side effects and limited efficacy, the plant derived

treatments were almost completely replaced by these synthetic drugs. The

main type of drugs used were anti-cholinergics because of their ability to

reduce muscle contraction. The most

widely used of them

was Benzhexol HCl, which had anti-cholinergic activity. It was marketed as

Artane in the U.S.A.. It was then the primary choice for treating

Parkinson's Disease. To a lesser extent

anti- histaminergics were also used for Parkinson's Disease. They lessened

the effect of allergic reactions, but also reduced muscle contraction.

Anti-histaminergic drugs were sold commercially, but only two of them,

diphenhydramine (Benadryl) and phenindamine (Theophorin), were widely used

in Parkinson's Disease.

The biochemistry of L-dopa

The underlying

biochemical changes in the brain were identified in the 1950s, due largely

to the work of Swedish scientist Arvid Carlsson (born 1923). In the 1950s,

Arvid Carlsson demonstrated that dopamine was a neurotransmitter in the brain and

not just a precursor for norepinephrine, as had been previously believed. He

developed a method for measuring the amount of dopamine in brain tissues and

found that dopamine levels in the basal ganglia, a brain area important for

movement, were particularly high. He then showed that giving animals the

drug reserpine caused a decrease in dopamine levels and a loss of movement

control. These effects were similar to the symptoms of Parkinson's disease.

Arvid Carlsson subsequently won the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in

2000 along with co-recipients Eric Kandel and Paul Greengard. The underlying

biochemical changes in the brain were identified in the 1950s, due largely

to the work of Swedish scientist Arvid Carlsson (born 1923). In the 1950s,

Arvid Carlsson demonstrated that dopamine was a neurotransmitter in the brain and

not just a precursor for norepinephrine, as had been previously believed. He

developed a method for measuring the amount of dopamine in brain tissues and

found that dopamine levels in the basal ganglia, a brain area important for

movement, were particularly high. He then showed that giving animals the

drug reserpine caused a decrease in dopamine levels and a loss of movement

control. These effects were similar to the symptoms of Parkinson's disease.

Arvid Carlsson subsequently won the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in

2000 along with co-recipients Eric Kandel and Paul Greengard.

The therapeutic

use L-dopa

These findings led other doctors

to try L-Dopa with human Parkinson's patients and found it to alleviate some

of the symptoms in the early stages of Parkinson's. Unlike dopamine, its

precursor L-Dopa could pass the blood brain barrier.

The validity of the approach was shown by the transient benefit seen after

injection of L-dopa.

However, it was not of practical

value as a treatment because of the severe toxicity associated with the

injection. At this point,

George C. Cotzias

(1918-1977)

made

a critical observation that converted the transient response into a

successful, large scale treatment. By starting with very small doses, given orally every two hours under continued observation, and

gradually increasing the dose he was able to stabilize patients on large

enough doses to cause a dramatic remission of their symptoms. Its findings

were

published in 1968. These findings led other doctors

to try L-Dopa with human Parkinson's patients and found it to alleviate some

of the symptoms in the early stages of Parkinson's. Unlike dopamine, its

precursor L-Dopa could pass the blood brain barrier.

The validity of the approach was shown by the transient benefit seen after

injection of L-dopa.

However, it was not of practical

value as a treatment because of the severe toxicity associated with the

injection. At this point,

George C. Cotzias

(1918-1977)

made

a critical observation that converted the transient response into a

successful, large scale treatment. By starting with very small doses, given orally every two hours under continued observation, and

gradually increasing the dose he was able to stabilize patients on large

enough doses to cause a dramatic remission of their symptoms. Its findings

were

published in 1968.

SINEMET AND

MADOPAR

There

were efforts to improve on the administration of L-dopa in order to lessen

its side effects. Dopa decarboxylase inhibitors reduced the metabolism of

L-dopa. L-dopa combined with the decarboxylase inhibitor carbidopa was

commercially launched in 1972 as Sinemet. Carbidopa made the product more

effective by delaying the conversion of L-dopa into dopamine until the

drug passed into the brain. The product was improved in 1991 when approval

was given for Sinemet CR, which is a controlled release version. The combination of L-dopa with the decarboxylase inhibitor

benserazide was commercially launched by Hoffmann-LaRoche in 1973 as

Madopar. It was eventually produced in a controlled release version

called Madopar CR.

MAO INHIBITORS

During

the 1970's, MAO inhibitors were introduced in order to prolong the effect

of L-dopa by delaying its breakdown. By inhibiting Monoamine Oxidase, MAO

inhibitors were shown to be able to raise dopamine levels, but the side

effects were severe. In 1968 it was shown that there were two MAO enzymes,

MAO-A and MAO-B. Inhibition of MAO-B was suitable for Parkinson's Disease.

The inhibition of MAO-B was not subject to the same risks as MAO

generally. The most suitable drug for use as a MAO-B inhibitor, called at

the time E-250, was launched commercially in 1977. Its use gradually

spread to other countries, but it was not approved in the U.S.A. until

1989. It came to be known as Selegiline. Since then, other MAO-B

inhibitors such as Rasagiline have been used in Parkinson's Disease.

DOPAMINE AGONISTS

Despite L-dopa

initially being seen as a major breakthrough, as many as 25% of people

taking L-dopa did not respond to it. Other people were being caused

widespread side effects due to using it, including dsykinesia.

Consequently, directly stimulating the dopamine receptors using dopamine

agonists appeared to some to be a better

option. Cotzias

demonstrated

efficacy using apomorphine in the treatment of Parkinsonism. When used

alongside L-dopa, its effects appeared to be additive. In 1974, another

dopamine agonist, bromocriptine, for the treatment of Parkinson's Disease,

was introduced. Following the initial success of bromocriptine, other

dopamine agonists were clinically trialled, including cabergoline, lisuride, pergolide, pramipexole, ropinirole, and

eventually, rotigotine. However, all of the dopamine agonists caused side

effects of their own.

FROM 2000 ONWARDS

From 2000

onwards, L-dopa primarily as Sinemet and Madopar was already being widely

used in the treatment of Parkinson's Disease, as were MAO-B inhibitors and

dopamine agonists. Even more variants of each or them were being used,

assessed or introduced. The primary new means of treating Parkinson's

Disease were different formats of L-dopa, including Rytary and

Numient, COMT

inhibitors, and Deep Brain Stimulation, which is quite an effective means

of surgery. Although Stem cell surgery had been claimed capable of curing

Parkinson's Disease it subsequently failed all its clinical trials.

Besides these methods there was a proliferation of new approaches to the

treatment of Parkinson's Disease that have become progressively more

diverse, but scientifically unsound.

After

thousands of years of describing and treating Parkinson's Disease, and

despite the enormous resources used in developing new treatments, each

method of treating Parkinson's Disease has been found to have serious

inadequacies. The ultimate therapy, one that was able to rid symptoms

without side effects is still to be revealed.

|

.gif)

.gif)

Charcot added to the list of symptoms the mask face, various forms of

contractions of hands and feet, akathesia as well as rigidity. It was only after Charcot gave a clinical lesson

in 1868 that the difference became clear (Charcot, 1868). In 1867 Charcot

introduced a treatment with the alkaloid drug hyoscine (or scopolamine)

derived from the Datura plant, which was used until the advent of L-Dopa a century later. In 1876 Charcot described a patient suffering from

Parkinson's disease in the absence of tremor, while rigidity was present. In

this case there was no paralysis, so Charcot rejected the term paralysis

agitans. Instead he suggested that the disease be referred to in future as

Parkinson's disease.

Charcot added to the list of symptoms the mask face, various forms of

contractions of hands and feet, akathesia as well as rigidity. It was only after Charcot gave a clinical lesson

in 1868 that the difference became clear (Charcot, 1868). In 1867 Charcot

introduced a treatment with the alkaloid drug hyoscine (or scopolamine)

derived from the Datura plant, which was used until the advent of L-Dopa a century later. In 1876 Charcot described a patient suffering from

Parkinson's disease in the absence of tremor, while rigidity was present. In

this case there was no paralysis, so Charcot rejected the term paralysis

agitans. Instead he suggested that the disease be referred to in future as

Parkinson's disease.

Although Charcot and Parkinson pointed out that

patients are moving slowly and with difficulty, they did not see this as a

symptom in its own right. The slowness of movement was firstly taken into

account by Claveleira and it became a new element of the definition. Jaccoud referred to this symptom in 1873 as akinesia.

In 1886, the neurologist and artist, Sir William Richard Gowers, drew an

illustration in 1886 as part of his documentation of Parkinson's Disease.

Cruchet introduced the word bradykinesia and emphasized that this symptom

should be mentioned in any definition of Parkinson's

disease.

Although Charcot and Parkinson pointed out that

patients are moving slowly and with difficulty, they did not see this as a

symptom in its own right. The slowness of movement was firstly taken into

account by Claveleira and it became a new element of the definition. Jaccoud referred to this symptom in 1873 as akinesia.

In 1886, the neurologist and artist, Sir William Richard Gowers, drew an

illustration in 1886 as part of his documentation of Parkinson's Disease.

Cruchet introduced the word bradykinesia and emphasized that this symptom

should be mentioned in any definition of Parkinson's

disease.  Its

symptoms were thought to encompass

almost anything imaginable. Encephalitis Lethargica could cause death in a

short period, or a type of sleep that might last days, weeks or months,

but could also cause insomnia. Many of those that survived developed Postencephalitic Parkinsonism. Encephalitis Lethargica consequently led to

a huge increase in the number of people with Parkinsonism. In the 1920's,

the majority of Parkinsonian patients had Postencephalitic Parkinsonism.

Its

symptoms were thought to encompass

almost anything imaginable. Encephalitis Lethargica could cause death in a

short period, or a type of sleep that might last days, weeks or months,

but could also cause insomnia. Many of those that survived developed Postencephalitic Parkinsonism. Encephalitis Lethargica consequently led to

a huge increase in the number of people with Parkinsonism. In the 1920's,

the majority of Parkinsonian patients had Postencephalitic Parkinsonism.